The ‘Individual Learning Plan’ units within the EAL Frameworks curricula at all levels (Access, Employment and Further Study) are the bane of many teachers’ existence. It’s often remarked that they are impractical and at odds with the ‘packaged’ units they are taught alongside. Delivery, unavoidably, happens in the context of a group - often times a large one - so in classes all students are (rightly or wrongly) assumed to be more or less at the same level and are collectively moved through language units with clear, common goals in sight.

In a ‘Standardised’ approach to teaching and learning, the elements for most units of language instruction are clear, envisaged outcomes are tangible, required skills are easily defined. But when it comes to those units about developing personal learning skills - it’s the ‘messy’ individual who is placed at the centre, in a position where things become a lot more difficult to nut out. How do we ascertain what the student needs or wants to learn and how does the teacher go about negotiating this within the context of as many as 20 other students with 20 other differing, individual learning plans?

I’m in agreement. There is something of a contradiction between this involved process of individual goal setting, articulation, development, review and documentation and the apparent impossibly of ever actually realising it in the context of the face to face classroom where time is in short supply and other units (which are much easier to deliver to the group) nonetheless must also be taught and assessed. “It’s a joke!” is the typical response of many frustrated and struggling teachers.

They have a point. How does the classroom teacher conceivably negotiate one-on-one, individual plans with as many as twenty students, monitor progress, review and adjust the plan while monitoring the process of all the others within the classroom context?

I dare say that under these conditions, the learning plans of the many are more likely to be ‘dictated’ rather than developed by the teacher at a single sitting. At best, some options can put forward to the group and individuals are encouraged to pick and chose and even copy those authored by the teacher. The follow up reviews are negotiated in the same vein - as long as the annoying assessment requirements can be got out of the way is all that matters.

This is not what an individual learning plan is meant to be about. And it is a pity considering the huge potential for genuine individual learning such a course of goal setting, study, review and reflection can achieve.

In the time of COVID-19 something has started to occur to me that I think is hard to appreciate in the fast lane of ‘real world’, face to face, classroom teaching. That is, the traditional classroom group is in many ways the problem and a conservative system in which summative assessment is king, distorts and works against any chance of individualised learning and gradual, formative assessment and development occurring.

Communications between the individual student and teacher remotely distanced from one another, on the other hand, provide an opportunity for this more intimate, one-on-one teaching and learning to take place. COVID has provided lots of time and breathing space for student and teacher to meet online, (or even just to talk by phone) about their learning, in a way that the time gobbling nature of a large class precludes. At least, this is how it appears to me.

There is also an element of bad timing when introducing learning plans. There are very few providers which introduce a substantial process of goal setting and developing an individualised plan at the time of a “Pre-Training Assessment” of skills. This would appear to be the logical or optimal time to combine assessing and goal setting. This is a “Zone of Proximal Development” that Vygotsky (1926) might describe as a moment to determine what the student can do and can’t do - as well as knowing what she wants to do and doesn’t - and to start erecting meaningful scaffolds for learning. The point is the process requires time, individual attention and appropriate scheduling.

The mammoth task usually falls to the teacher to get underway at the start of a term - usually during the first week of classes - when she is preoccupied initiating her students into the course and getting the ‘real’ teaching underway. There’s no time to waste and little freedom to cater to individual needs - the assessment schedule has been determined and must be met. The class is swept along from one week to another, from one assessment task to the next ...but the learning plan seeking some complex individual time and interaction, is barely touched.

What occurs to me from this period of online teaching is that the structures of learning: the timetabling, the configurations of traditionally delivering to a large number of students all at once in classrooms largely happens at the expense of denying time for dialogue between teacher and individual students. We need to dramatically renovate our teaching and learning arrangements and architecture - from the way we manage the time available to us to the ‘real’ and virtual environments we use.

In a ‘Standardised’ approach to teaching and learning, the elements for most units of language instruction are clear, envisaged outcomes are tangible, required skills are easily defined. But when it comes to those units about developing personal learning skills - it’s the ‘messy’ individual who is placed at the centre, in a position where things become a lot more difficult to nut out. How do we ascertain what the student needs or wants to learn and how does the teacher go about negotiating this within the context of as many as 20 other students with 20 other differing, individual learning plans?

|

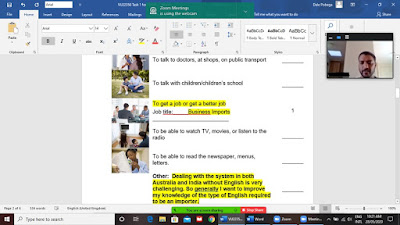

N. talks about the cultural and language obstacles he faces - s well as his strengths and advantages - in becoming an importer of oil from India. |

I’m in agreement. There is something of a contradiction between this involved process of individual goal setting, articulation, development, review and documentation and the apparent impossibly of ever actually realising it in the context of the face to face classroom where time is in short supply and other units (which are much easier to deliver to the group) nonetheless must also be taught and assessed. “It’s a joke!” is the typical response of many frustrated and struggling teachers.

They have a point. How does the classroom teacher conceivably negotiate one-on-one, individual plans with as many as twenty students, monitor progress, review and adjust the plan while monitoring the process of all the others within the classroom context?

I dare say that under these conditions, the learning plans of the many are more likely to be ‘dictated’ rather than developed by the teacher at a single sitting. At best, some options can put forward to the group and individuals are encouraged to pick and chose and even copy those authored by the teacher. The follow up reviews are negotiated in the same vein - as long as the annoying assessment requirements can be got out of the way is all that matters.

|

In this guided dialogue, N. adapts a model text about dimension, weights and measures to describe the products he is interested in importing |

This is not what an individual learning plan is meant to be about. And it is a pity considering the huge potential for genuine individual learning such a course of goal setting, study, review and reflection can achieve.

In the time of COVID-19 something has started to occur to me that I think is hard to appreciate in the fast lane of ‘real world’, face to face, classroom teaching. That is, the traditional classroom group is in many ways the problem and a conservative system in which summative assessment is king, distorts and works against any chance of individualised learning and gradual, formative assessment and development occurring.

|

At this stage, Dale introduces the subject of "specifications" or "specs" so N. can practice the language of comparisons. All the while Dale is recording the session, note taking and observing. |

Communications between the individual student and teacher remotely distanced from one another, on the other hand, provide an opportunity for this more intimate, one-on-one teaching and learning to take place. COVID has provided lots of time and breathing space for student and teacher to meet online, (or even just to talk by phone) about their learning, in a way that the time gobbling nature of a large class precludes. At least, this is how it appears to me.

There is also an element of bad timing when introducing learning plans. There are very few providers which introduce a substantial process of goal setting and developing an individualised plan at the time of a “Pre-Training Assessment” of skills. This would appear to be the logical or optimal time to combine assessing and goal setting. This is a “Zone of Proximal Development” that Vygotsky (1926) might describe as a moment to determine what the student can do and can’t do - as well as knowing what she wants to do and doesn’t - and to start erecting meaningful scaffolds for learning. The point is the process requires time, individual attention and appropriate scheduling.

The mammoth task usually falls to the teacher to get underway at the start of a term - usually during the first week of classes - when she is preoccupied initiating her students into the course and getting the ‘real’ teaching underway. There’s no time to waste and little freedom to cater to individual needs - the assessment schedule has been determined and must be met. The class is swept along from one week to another, from one assessment task to the next ...but the learning plan seeking some complex individual time and interaction, is barely touched.

What occurs to me from this period of online teaching is that the structures of learning: the timetabling, the configurations of traditionally delivering to a large number of students all at once in classrooms largely happens at the expense of denying time for dialogue between teacher and individual students. We need to dramatically renovate our teaching and learning arrangements and architecture - from the way we manage the time available to us to the ‘real’ and virtual environments we use.

Kalantzis and Cope (‘Literacies’ 2020) have drawn attention to the great results in learning and enhanced mechanisms for assessment that can be gained by reorganising classes through online learning into flatter, more engaged, collaborative and communicative smaller groups where teacher input can be less intrusive and more strategic. If such a model can work it would also provide the teacher and an individual student some much needed time and space to conference more privately and meaningfully about what and how the learner might want to learn. Does dramatic change in group learning provide the necessary conditions for individuals to take greater control and for learning plans to actually begin making sense? Could a model of organised learning - whether it be wholly online or blended - which provides flexibility, a liberal time frame, freer study choices and opportunity for a greater range of interactions, activities and roles to be negotiated between teacher and students be the answer?

No comments:

Post a Comment